Find us on Facebook

|

HOME > Article Paul Von Blum

| | |

|

|

Jamaican Sources and

African American Visions:

The Art of Bernard Hoyes

By Paul Von Blum, J.D.

Lecturer UCLA

|

|

The diverse community of African American visual artists in Southern California includes men and women of all ages and origins. Many, especially those of middle age and older, have come from the American South. Their early experiences deeply inform their work, providing a compelling foundation for their unique creative visions. Such Los Angeles-based luminaries as Samella Lewis, John Outterbridge, Ernie Bames, William Pajaud, Roland Charles and others draw heavily on their Southern roots to document and celebrate African American life and culture. Still other African American artists have resided most of their lives in the Los Angeles area. They too reflect their origins in their work. The artistic visions of Betye, Alison, and Lezley Saar, Varnette Honeywood, Charles Dickson, Richard Wyatt, Willie Middlebrook and many others are rooted in their creators' early Southern California experiences. Their engaging paintings, prints, sculptures, and installations reflect the complex racial, social, and spiritual tensions of Los Angeles from the mid -20th century to the present.

The region also has a thriving West Indian population. Their distinguished contributions to regional black life includes, among many others, major accomplishments in commerce, politics, and expressive culture, including the visual arts. A key contemporary figure is Bernard Stanley Hoyes, whose paintings, murals, and prints recall his African Caribbean roots and add further luster to the dynamic growth of African American art in Los Angeles. Exceptionally talented and highly prolific, Hoyes has achieved national and international visibility throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Widely exhibited and collected, he has also received extensive and favorable critical attention for his imaginative interpretations of life in his native Jamaica and in the United States.

Bernard Hoyes's journey from childhood to his mature artistic career has rarely been easy. Born in Kingston, Jamaica in 195 1, he grew up in a close-knit community. Decades later, he recalls vividly the exciting activity and tough streets of the Jamaican capital city. From early childhood, he regularly encountered foreign visitors, many of whom became customers for his youthful artistic creations. Like most major artists, Hoyes discovered his own talent early, actually beginning his visual career at the age of nine. He studied at the Junior Art Centre of the Institute of Jamaica. His mother worked for the Jamaica Tourist Board, placing her in an advantageous position to bring her son's work to a wide and relatively affluent audience. The sale of his carvings and watercolors helped launch him into a lifelong dedication to artistic creation and dissemination.

Several other features of life in Kingston provided the thematic foundation for his mature work as a painter and printmaker. The vibrant markets and the colorful fishing villages left an indelible, lifelong impression on Hoyes. So too did the rituals and ceremonies of the Jamaican revival cults and the ubiquitous presence and impact of the Rastifarian community. These memories have informed his artistic productivity throughout his life, making him one of the most widely known and appreciated African American artists of Caribbean origin.

At the same time, the young artist had to contend with the more troublesome features of life in Kingston. He experienced the ubiquitous political turmoil and violence that long dominated Jamaican society following its independence from Great Britain. Street battles resulting in injuries and death were all too common, compounding the difficulties of grinding poverty and inadequate economic opportunity for the majority of the Jamaican population. More personally, Bernard Hoyes had to learn to live by his wits in the face of the growing crime and gang activity he encountered every day. Shootings and knifings were routine and he found himself getting caught up in the dangerous street life of his native city.

Continuing in this mode would have been problematic at best, inevitably aborting the development of his artistic talent. Understandably fearful, his mother resolved to give him an opportunity to build a more productive life outside the specter of youthful violence and even the possibility of incarceration or death. When he was fifteen, Hoyes was sent to New York, where he lived with his father in Brooklyn and resumed his formal education, especially in art. In high school, one of his teachers quickly recognized Hoyes's abilities and assisted him in obtaining further training at the Art Students' League. There he learned painting and sculpture in the evenings. He also met and studied with such major African American artistic figures as Norman Lewis, Hughie Lee-Smith, and Romare Bearden.

In 1968, he received a Ford Foundation Scholarship that enabled him to attend a summer program of the Vermont Academy in Putney, where he also worked closely with professional artists. He also finished his academic work at that institution, where he developed the intense drive for success that has pervaded his subsequent life and career. At Vermont Academy, he struggled to find time for his own artwork, managing to build an impressive portfolio and completing his high school education with an exhibition at the campus art gallery.

By his late teens, Hoyes had already determined that he wanted to live his whole life as an artist. After applying to several colleges, he was accepted at the California College of Arts and Crafts in Oakland. During his four year B.F.A. studies there, he honed his artistic skills, finding generally excellent instruction there, especially in drawing. During his time as a painting and design student, he produced a large body of work. He also encountered the first major expression of racism in his life. While learning the art and craft of sculpture, he discovered that some racist white workers in the college foundry had on occasion destroyed his works because of their animosity towards blacks.

Augmenting his formal artistic education, Hoyes developed strong ties to the Bay Area African American community, an identification that similarly pervades his mature work as a visual artist. Among other things, he assisted in the Black Panther breakfast program of that era. Through that community service, he also met Emory Douglas, the chief artist of the Black Panther Party, whose posters and graphics exemplify the black pride and political militancy of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Following his graduation from the California College of Arts and Crafts, the artist remained in the Bay Area, living first in Oakland and then in San Francisco. There he established a studio to pursue his goal of becoming a full-time artist. After a brief return to Jamaica, he moved to Los Angeles in 1975, continuing his efforts as a struggling artist and finding work as a designer and art director for the California Museum of Science and Industry. His efforts in that setting were fulfilling, encouraging him to draw strongly on his artistic training and creative inclinations. Still, he found that even this work deflected him from his deeper ambitions and aspirations: to work entirely as a creative artist, a path established much earlier during his formative years in Kingston, Jamaica.

Despite the pleas of colleagues and institutional superiors, Bernard Hoyes resigned his position at the Museum and established his own studio in central Los Angeles. He immersed himself in his art, producing a large body of paintings and other work. He also became active in local arts organizations, establishing a growing reputation in the large community of visual artists of all racial and ethnic backgrounds in greater Los Angeles. Over the years, he has managed to survive effectively in his chosen calling. Beyond producing his own original paintings and prints, Hoyes has also formed the Caribbean Cultural Institute and Caribbean Arts, Inc. to expose and advance Caribbean culture to audiences in the United States. The Institute promotes classes, workshops, and cultural events focused primarily on Afro-Caribbean themes. Caribbean Arts is his publication company that disseminates Hoyes's limited edition lithographs and serigraphs as well as his functional artwork such as his "Kwanzaa Holiday" and other note card series.

Throughout his artistic career, Bernard Hoyes has given exceptionally serious thought to the complex influences that have helped to shape his distinctive visual style and his lifelong commitment to creative pursuits. He credits his Art Students' League teacher Norman Lewis in particular for helping him develop an enduring sense of what it takes to be an artist--a vision of character and perseverance in the face of inevitable frustration and rejection in a society that has historically marginalized the arts in its hierarchy of values and priorities. He also credits Jacob Lawrence and several Haitian painters for their inspiration in encouraging him to use the bold colors that have characterized his works for more than 25 years. And he acknowledges such disparate figures as Romare Bearden, Henry Matisse, and Pablo Picasso for encouraging his own energy, versatility, and productivity.

Hoyes is similarly indebted to the exemplary tradition of Jamaican art. He cites such major Jamaican figures as Barrington Watson, Christopher Gonzalez, Gene Pearson, and Osmond Watson, the artist for whom he expresses special passion. Hoyes's own artwork both reflects and augments that Afro-Caribbean tradition. Both thematically and stylistically, his paintings and prints reveal a strong and enduring link to his Jamaican heritage, a background for which he is openly proud.

The artist is similarly articulate about the complex philosophy underlying his artistic productions. Above all, Bernard Hoyes communicates an Afrocentric perspective that links his entire work from the early 1970s to the present. He employs symbols of his people's ancestral origins in order to uncover the gaps between what people know and what they should know about the resilience and strength that Africans have demonstrated in their survival in the Western world. Hoyes has resolved to present images of Afro-Caribbean and African American dignity to his viewers, revealing that these historic "others" retain a remarkable grace and spirituality given the oppression and hardships they have faced for hundreds of years. Like most African American artists, he eschews an "art for art's sake" ideology, seeking instead to combine rhythmical and colorful compositions to record and celebrate the glories of the life and culture of the African Diaspora.

|

|

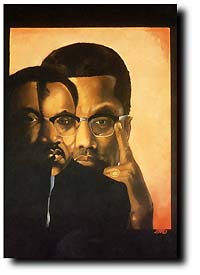

Over the years, Hoyes has moved thematically from a social and political perspective to what he sees as a deeper spiritual focus. Many of his initial works reflect the powerful social vision that has characterized some of the finest African American art from the Harlem Renaissance through the 1990s. One of his earliest oil paintings communicates a vision that even now resonates with millions of African Americans and others who continue the struggle for racial justice and equal opportunity. "One Vision" (Figure 1), painted in 1970, is a portrait that imaginatively fuses two of the greatest African American leaders of the 20th century: Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X. Each man retains his unique identity in this work; viewers have no difficulty in discerning both individual portraits in the composition, a visual highlight that reinforces the moral and political seriousness of the underlying message.

|

One Vision

(Figure 1)

|

|

|

|

The striking aesthetic quality of the painting engages its viewers, encouraging thoughtful reflection about "One Vision's" profound meaning and implications. Like many African Americans, Bernard Hoyes experienced the disconcerting media distortions of the life and work of both King and Malcolm following their untimely assassinations. Although both men were widely vilified during their lives, Dr. King was canonized after his death in the mass media as the symbol-at times the only symbol--of the civil rights struggle. Journalists and other pundits depicted him as the "good" black leader, dedicated to peaceful and nonviolent protest. The same media demonized Malcolm X (before and after his death) as the "dangerous" black leader, dedicated to violence and anti-white attitudes and actions. This false dichotomy has largely persisted in the American national consciousness for three decades. Millions of American students and others uncritically believe that Martin Luther King and Malcolm X were entirely opposite from one another, each committed to radically opposing American racial visions and policies.

The artist uses his work to dispel such simplistic perceptions. By joining both leaders in one portrait, he provides a more realistic assessment of the legacy of these giant liberation figures. The portrayal suggests, on the contrary, that King and Malcolm shared a deeper basic vision for their people's future. Hoyes reveals that despite their significant philosophical and strategic differences, both men expressed far greater similarities about America's pervasive injustices toward its African American inhabitants--in short, one fundamental vision of justice and dignity. Both, moreover, courageously advocated policies to close the gap between American racial ideals and American racial practices. Significantly, Hoyes places Malcolm in the center of the composition, a gesture of artistic affirmative action that restores him to the rightful and more equitable historical stature he properly deserves.

|

|

|

|

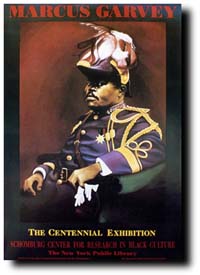

Marcus Garvey

(Figure 2)

|

In 1980, Hoyes added to his visual celebration of major figures of African nationalism. His portrait of Marcus Garvey (Figure 2) is a respectful vision of one of the most controversial black leaders of the 20th century. The leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in New York, Garvey played a powerful role in African American political life in the teens and twenties, especially in Harlem. Believing that blacks would never receive fair treatment and equity in the United States, Garvey advocated a massive return to the African homeland from which his people were so violently removed. Although many African American leaders, especially W. E. B. Du Bois, opposed Garvey's plan, UNIA developed a large and passionate following of approximately two million, mostly poor urban blacks expressing hope and seeking justice in a racist society.

|

| Hoyes's portrait must be viewed in its subject's specific historical context. Like many other militant black leaders in the United States for hundreds of years, Marcus Garvey was both persecuted and prosecuted in America, serving time in a federal prison. He was widely condemned by the authorities and largely written out of the history books. Following his release, he returned to his native Jamaica, where he has become a major national hero and source of extraordinary national pride.

|

|

|

Redemption Song

|

|

| Like hundreds of African American artworks, this painting serves as a major historical corrective, imbuing dignity and honor to an historical figure largely denied such recognition in mainstream American communications and educational institutions. Also reproduced as a poster, the work highlights Garvey in his full UNIA regalia. His determined expression underscores his sustained commitment to the welfare of people of African descent. Above all, the portrait communicates the major accomplishment of Marcus Garvey: his remarkable ability to provide hope and instill pride to millions egregiously denied this fundamental human right. Now in the permanent collection of New York's Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the painting was also selected by UCLA History Professor Robert Hill and the University of California Press for the cover of the 10-volume work on the papers of Marcus Garvey and the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

|

|

| In the initial stage of his artistic career, Bernard Hoyes embarked on one of his most dramatic and enduring efforts. After he left his museum position, he created a new aesthetic style to express the ancestral themes that had come to occupy much of his personal and professional attention. His "Rag Series" involves a spontaneous technique resulting in a unique vision linking the past and the present. He casts a rag laden with ink onto various surfaces, much like a fisherman casts a net into the sea. He then redesigns the imprint that remains into figurative forms expressing such themes as poverty, racial prejudice, panic, and emotional confusion. The emerging male and female figures are trapped in the net, but struggling mightily to free themselves. The "Rag Series" is done in muted sepia tones, black and white, and metallic silver and gold, in order to accentuate the visceral impact on viewers. Hoyes premiered this series in 1979 at the William Grant Still Arts Center in Los Angeles, a key institution highlighting the works of African American artists in the region.

|

|

|

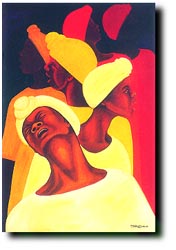

She Found Wings in Rags

(Figure 3)

|

A typical work from this series is "She Found Wings in Rags" (Figure 3). One of the artist's personal favorites, this effort exemplifies his fundamental artistic vision and philosophy. Here the woman figure reveals a striking grace and dignity despite the severe poverty and other hardships she has likely encountered throughout her life. Whatever the barriers, she not only survives but thrives. Her spirit soars as she dances boldly in the face of adversity. The woman signifies the extraordinary ability of an entire people to endure, adapting to the myriad cultures and demands of multiple nations and languages throughout the African Diaspora. Replicated in serigraph form in 1992, "She Found Wings in Rags" focuses on one human being, encouraging audiences to humanize and personalize the strength and accomplishments of black people in general and black women in particular.

|

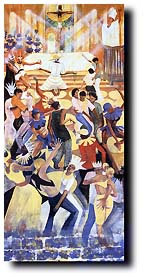

| Throughout his professional career, Hoyes has produced a vast array of paintings and prints that evoke memories of the vitality of his native Jamaica. These works represent the signature style of his mature career. Highly energetic, they combine dynamic motion and vibrant color to provide insightful glimpses into Afro-Caribbean religion, dance, music, and other elements of daily life. "Hymn in the Night" (Figure 4), for example, highlights the ritual theme that pervades Jamaican culture and the artist's own consciousness. Painted in Hoyes's desert studio in 1993 and replicated in serigraph form in 1996, it is dominated by the rhythmic dancing of several figures. The artwork focuses on how the spirits take possession of the people and highlights their immense emotional responses to theses religious experiences. It also emphasizes the powerful African sources of Jamaican spiritual beliefs and practices. The artist's effective use of reds and yellows accentuates the subject matter's intensity and emotion. Worship is conducted in outdoor settings, where people view the spirits as more accessible. Viewers of "Hymn in the Night" and many of Hoyes's similar artworks have entree into the essence of Afro-Caribbean life, a vision largely absent in conventional tourist visits and in most media accounts of Caribbean society.

|

Hymn in the Night

(Figure 4)

|

|

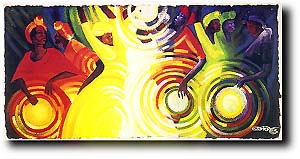

"Tambourines, Talking Drums, and Smoke Signals"

(Figure 5)

|

"Tambourines, Talking Drums, and Smoke Signals" (Figure 5) is a more visually complex work about ancestral origins and its significance for the population of the African Diaspora. Painted in 1991 and reproduced as a poster in 1994, the effort reflects Bernard Hoyes's increasing focus on deeper spiritual elements of the Afro-Caribbean and African American experience. His vibrant use of reds, yellows, and greens draws instant audience responses. The dynamic movement of the female figures works harmoniously with the swirling rhythm of the music they produce on the tambourines and drums. The painting's sheer energy signifies the power of African expressive arts, especially music. These instruments of sound have been used for thousands of years to communicate over long distances.

|

| The work reminds African American viewers of their own ancestral roots and invites others to celebrate the majesty of African cultural history. Like many other African American artists, Hoyes places strong emphasis on the value and significance of music. Many of his predecessors and contemporaries have properly focused on spirituals, jazz, blues, hip hop, and other specifically African American musical forms. He himself has produced an outstanding jazz series entitled "Jazz Suites," focusing on saxophone players in a style combining his traditional motion and color with almost abstract composition. Hoyes's own visual evocation of the specifically African musical sources in "Tambourines, Talking Drums, and Smoke Signals" adds a valuable dimension to this influential and recurring artistic motif.

|

Jazz Suite-Tenor Sax

|

|

victory over Sin

|

In the 1990s, Hoyes has also turned his attention to the redemptive power of visual art. He knows well the difficulties of contemporary urban life, especially for people of color. Having lived both in Kingston, Jamaica and Los Angeles, he has experienced first-hand the oppressive realities of poverty, racism, and urban warfare. He understands the problems and terrors of the street and the dangers lurking for young people in particular. Using his art to offer an alternative vision, he has produced some outstanding public artworks in both locations that offer hope and healing rather than strife and conflict.

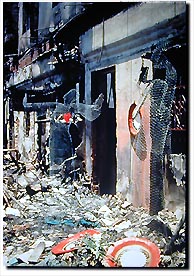

Bernard Hoyes has returned regularly to Jamaica, rediscovering his personal origins and renewing his artistic creativity. In 1992, he found a dramatically non-traditional exhibition space in downtown Kingston for a mural project he executed with fellow artist Andy Jefferson. This project, "Casualties of Contemporary Life," called attention to the physical, social, and spiritual suffering of downtown residents. Painting in a burnt-out building (itself a casualty of the 1977 insurrection there), the artists invited city residents to experience the aesthetic pleasure and emotional and intellectual satisfaction of first-class art in such an unlikely setting. Hoyes's own works in that environment focus on the dignity of labor, the power of spiritual forces over sin and weakness, and the unity and solidarity of the people.

|

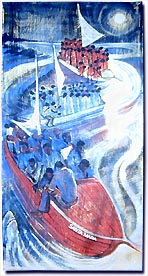

| In one 5' by 10' panel, he emphasized the broader struggles of Afro-Caribbean peoples in the late 20th century. "Haitian Boat People" (Figure 6) evokes memories of the pervasive human consequences of recent political turmoil and oppression in neighboring Haiti. The terror and brutality of the two Duvalier regimes and of the military caste that overthrew President JeanBaptiste Aristide and the grinding economic deprivation have fostered illness, death, and pervasive despair.

In recent years, many thousands of Haitians have fled their homeland, often in rickety boats that often fail to complete their journeys. Many--too many--have died at sea. Those who survive sometimes arrive in Florida, where they are swiftly detained by U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service officers and incarcerated and even returned to perilous and uncertain fates in Haiti. Hoyes's mural imbues them with a human face that negates their invisibility and marginality throughout the world. The blunt reality is that no country wants these black refugees from political and economic despair; American xenophobia and racism are particularly effective barriers to their desperate quest for better lives. "Haitian Boat People," like all humanistic artworks, encourages viewers to substitute compassion for apathy and ignorance. The artist uses his characteristic color scheme, swirling movement, and visual detail effectively in this panel. The bright moonlight in the upper right comer signifies the possibility of hope and transformation, a profound visual response to official callousness and human cruelty. This mural panel joins a distinguished tradition of African American visual art in addressing human problems that both incorporate and transcend race alone.

|

Haitan Boat People

(Figure 6)

|

|

Apparition of Healing Spirits

|

Ironically, Bernard Hoyes returned to Los Angeles from Kingston during the week of the 1992 urban rebellion. Drawing on his recent Jamaican experiences with "Causalities of Contemporary Life," he again turned to his art in order to contribute to the healing process. He mounted his "Apparition of Healing Spirits" at several fire bomb sites throughout the devastated South Central Los Angeles area. Radically different from his paintings and prints, this installation involved transforming wire mesh into transparent figures, accompanied by ceremonial platters and fresh flowers and fruits. His objective was to offer art as a magical presence in simmering and desolate spaces following the violence and destruction of the immediate past.

Like all the individual works in this effort, "Love Lure" (Figure 7) stayed up for only a week. Knowing that the Los Angeles civil unrest reflected deep historical anger, alienation, and despair among African Americans and other residents of color, the artist sought to interject a visual sign of love in this desolate environment. A figurative presence in such an unlikely setting inevitably compels viewers to do a double take, encouraging a vastly different consciousness from what one would inevitably expect when confronting such massive physical devastation. Walking amidst the burnt-out buildings and litter-strewn lots, hopelessness only intensifies, exacerbating the overall sense of human misery.

|

| Hoyes's healing spirits, however, allow people to smile--and even imagine a future. A simulated human presence, with a colorful heart in its center, signifies the possibility of a new beginning. Even a reaction of laughter or incredulity is a valuable antidote to despair. Hoyes understands, to be sure, that art alone can scarcely reverse the structural inequalities of wealth and power and the gnawing persistence of racism that catalyzed the Los Angeles revolt. But without some sense of healing and hope, few residents can even imagine commencing the hard work of political and economic transformation required for a truly just society. Art, at least, signifies the triumph of life over the death of the human spirit.

Hoyes has always had a profound commitment to community service, using his art to promote unity and cooperation among people of different backgrounds. In 1990, he embarked on an ambitious mural project at the First African Methodist Episcopal Church (FAME) in Los Angeles. Entitled "In the Spirit of Contribution," this massive 120' by 6'10" effort details many of the accomplishments of African Americans and Latinos throughout the history of the United States. Like most community mural projects, this effort involved a close collaboration between the artist and young people from the surrounding community. In this instance, Hoyes worked with black and Latino gang members, seeking to encourage both groups to understand and appreciate each other's contributions to the spiritual life and growth of American society

|

"Love Lure"

(Figure 7)

|

|

(Figure 8 A-C)

|

| The left side of the mural is dedicated to African American history and luminaries, including jazz legend Duke Ellington, dancer "Bojangles" Robinson, artist/activist Paul Robeson (Figure 8A), Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, and singer Marian Anderson. While all these figures are well known generally, they need constant exposure to young people whose educational experiences regularly exclude the giant figures of African American history and culture. The portrayal of Paul Robeson in this panel is especially noteworthy; Robeson's egregious exclusion from the history books following his blacklisting during the infamous era of McCarthyism continues to impede the development of a fairer and more comprehensive historical perspective. Like many African American muralists, Hoyes is dedicated to using his artwork as a valuable alternative to historical parochialism.

Another section of the FAME mural adds further value to this deeper educational objective. Figure 8B highlights the historic black power protest of U.S. runners John Carlos and Tommie Smith during the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City. The two athletes stand firm in informing the world about the long history of racism in their native lands. Hoyes and his youthful assistants strategically place Carlos and Smith between three female dancers, whose poses obviously signify celebration and honor for the dramatic gesture of the black power salute. At the time, the two medal-winning black athletes were dismissed from their Olympic team and sent back to the United States. They were also widely condemned in the press and suffered severe personal hostility and professional harm. This mural section provides another dramatic contrast to official versions of history. Countering the conventional condemnation for this heroic act, the mural instead presents the act as a moral highlight of the modem Olympics.

The right side of "In The Spirit of Contribution" includes prominent Mexican and Chicano heroes, including agrarian revolutionary Emiliano Zapata, 19th century President Benito Juarez, artist Frida Kahlo, and labor leader Cesar Chavez. The section emphasizing Kahlo and Chavez (Figure 8C) again reflects Hoyes's traditional color scheme and composition. Thematically, it brings major figures of cultural and political life to wide community audiences. Like the African American sections, this also provides a useful educational service to young people whose backgrounds reflect the still dominant educational focus on the contributions of affluent white men.

In the late 1990s, Bernard Stanley Hoyes remains committed to his personal quest to lead a full and active artistic life. Working energetically in his studios in Los Angeles, Desert Hot Springs, and occasionally in Kingston, Jamaica, he brings a durable and engaging Afro-Caribbean sensibility and spirit to the talented community of black artists in Southern California. His remarkable vision attracts viewers of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, especially those who respond intuitively to the colorful dynamism of his paintings and prints. Combining technical excellence and an undaunted entrepreneurial zeal, he has had a regional, national, and international impact despite his relative youth. In 1995, he presented an exhibition at the Watts Towers Art Center in celebration of 25 years of artistic accomplishment. Few who attended had any doubt that many chapters were yet to come.

|

| |

| | |

|

|

|